The room where Ford cars of tomorrow are fine-tuned is a three-sided box with projectors throwing images on to each wall and the ceiling. Mounted in the middle is a dummy car interior.

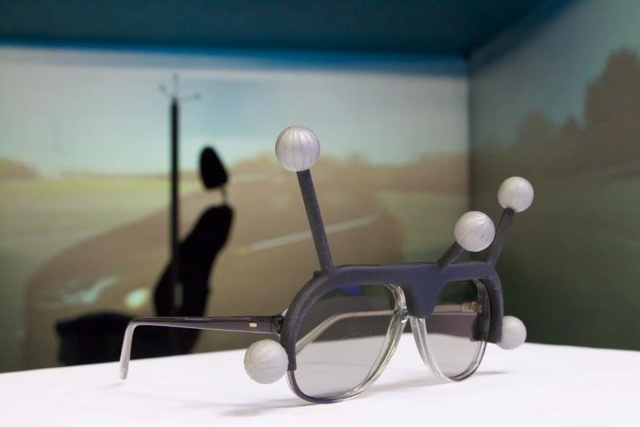

Climb into the car’s seat, slip on 3-D glasses framed with motion detectors, and the screens instantly melt into a hyper-realistic virtual world where you find yourself immersed in the computer-simulated interior of a new car.

Ford calls it the 3-D CAVE and it has changed the way cars are designed and refined. Rather than building multiple real-world vehicle prototypes – a time-consuming and resource-intensive process – Ford uses the 3-D CAVE to test and refine thousands of details of new car designs from the size and position of a cup-holder to rear-window visibility.

“We can now conjure up a car in the digital world, and then actually get in and experience it,” said Michael Wolf, virtual reality supervisor, Ford of Europe.

“We still rely on the know-how and imagination of our prototype engineers to bring designs accurately to life, but now they have at their disposal a much more sophisticated tool to do so.”

Engineers using the 3-D CAVE in Cologne, Germany, sit in a dummy car interior as vehicle 3-D simulations are projected on to the ceiling and three surrounding walls.

Wearing special polarising glasses and monitored by a motion-detecting infra-red system, they interact with the virtual vehicle by, for example, determining the reach to rear view mirrors or to place bottles into door pockets.

The CAVE uses an animated external environment with pedestrians and cyclists to help engineers assess visibility of the outside world from inside the car.

It also enables engineers to access and compare at the push of a button multiple designs – including vehicle interiors produced by other manufacturers.

The CAVE in Cologne is supported by an identical set-up at Ford HQ in Dearborn, Michigan, and further single-wall facilities make it much easier to move prototypes around the world.

Engineers used the CAVE to identify the potential of hinged front doors and sliding rear doors in the B-Max people-mover.

It also helped ensure the rear quarter window offers the best view for driving in urban conditions, and 3-D simulations of different windscreen wiper approaches enabled engineers to identify the “butterfly” system – whereby the wipers move in opposing directions – as providing best visibility.

For the Focus, Ford used the CAVE to optimise windscreen wiper effectiveness; to maximise roominess for rear passengers by testing designs for the front seats and headrests; to evaluate door frame design impact on visibility; and to minimise reflections that can affect the view through windows and of information displays.

“The CAVE makes it so much quicker and easier to analyse designs,” said supervisor Wolf. “For example, to manufacture three different front pillar design examples and fit them to a prototype vehicle could take 10 days.

“The same project could be completed in just one or two days using our virtual reality simulator – and also saves physical resources.”

For those occasions when only a physical component will do, Ford 3-D printing places thousands of ultra-fine layers of material on top of each other to form complex shapes and designs. 3-D printing components can comprise up to three different types of resin that enable hard and soft sections within a single object, and can measure up to 700 mm.

Ford used 3-D printing to produce a door handle and seat panels for the new B-MAX, and front pillar trim and tailgate bump stops during development of the new Kuga. Ford is now researching potentially producing large volume car parts using the technology.

“3-D printing means we can create all kinds of complex shapes and one-off components that would previously have required many man-hours and resources to produce manually or through machining,” said Sandro Piroddi, supervisor, Rapid Technology, Ford of Europe. “It has huge potential for Ford vehicle production in the future.”