Gear Patrol magazine’s Bryan Campbell says that when it comes to cars, size matters

The car market of 20-years ago is almost unrecognisable when you consider today’s automotive landscape.

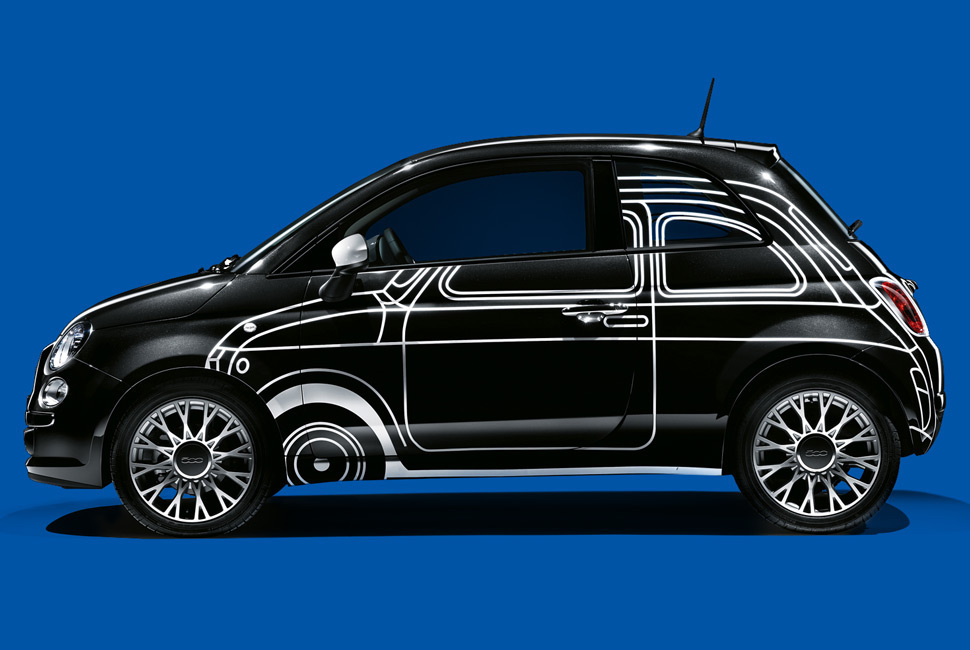

Compare the illustration above of the original Fiat 500 with the current one. The race to fill even the smallest gap in the market is being led by the Germans, creating cars no one really asked for.

BMW alone has tripled the number of different cars it makes, saturating (and simultaneously diluting) their lineup with new models ranging from a handful of track-focused SUVs to head-scratchers like four-door versions of a two-door car that is itself based on a four-door car.

And with each replacement model size increases, causing BMW and the like to create new smaller models to fill the hole the old model grew out of.

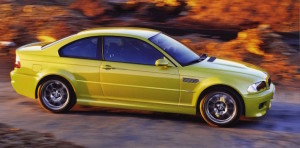

For the best example look no further than the 2016 BMW M2. The M3 has outgrown the segment it helped define; the smaller M2 and the 1M are now there to fill the gap in the market.

As the Germans lead the march to overpopulate product lines, the rest of the world is following suit. Cadillac’s CTS has gone from competing against the BMW 3-Series to going up against the 5-Series.

The Mini has grown a metre and doubled in weight since the original was introduced. Cars in general are ballooning in size, and if you’re on the market for a sporty new drive bigger isn’t always better.

In the past two decades almost every performance-focused car on the market has inflated in size, which goes against the very ethos of the performance car.

Colin Chapman, founder of Lotus Cars, famously said: “Adding power makes you faster on the straights. Subtracting weight makes you faster everywhere.”

Chapman may have coined the phrase, but every designer who has put pencil to paper with intentions to draw up a sporty car can’t deny those words.

Of course the (US) National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has tightened its grip on car design by introducing more stringent requirements and restrictions governing every car that hits the road, such as larger crumple zones and massive pedestrian crash clearances.

The latter produces the biggest effect on overall design and weight. A minimum distance of 243mm is required between the underside of the bonnet and the highest hard point in the engine bay.

If that seems like a quick fix, it’s not. Once the general shape of the front of the car has changed, it has a trickle down effect through the rest of the car.

The higher bonnet means a higher windshield; the higher windshield means a higher roof; the higher roof means a higher beltline and a higher beltline means bigger doors, bigger wheel arches and bigger wheels. More metal means more weight.

BMW are the biggest culprits in taking an iconic sporty sedan — specifically the 3-Series — and inflating it to comical proportions, all the while insisting it has the DNA of the original.

The third-generation 3-Series, made in the 1990s, had a 2693mm wheelbase, was about 4420mm overall, and weighed around 1365kg. The current production 3-Series has a wheelbase of 2920mm, measures 4724mm overall and weighs in at 1623kg.

But, take a look in any direction in the segment: at Audi, Mini, even the Honda NSX: the size and weight gain seems contagious.

Sure, each of theses cars’ newest iterations are faster than the past generations, despite the weight gain, but each new version has gotten a bump in power. The first generation 3-Series had 66kW, the current generation has over 225kW.

If the reason for some of last century’s most iconic sports cars becoming bloated is for safety, than it would be hard to argue. Safety should come first. After all, we’re out there to have fun and enjoy the drive and it’s better to arrive late than not at all.

But if there’s a shining example of a company can keep a car small and exciting it’s the Mazda MX-5. The newest generation MX-5 is only 25mm longer than the original and is actually lighter than the second-generation model.

Yet it’s still a safe car. Mazda went so far as to lower the power of the latest MX-5, just so it could keep the right power-to-weight-ratio, which is the crux of any true performance car.

BMW seems aware of their misdeeds, insofar as the M2 is, dimensionally, almost dead-ringer for the E46 M3.

So it is possible, when you’re not chasing volume sales or that extra few millimetres of legroom every year, to engineer your way around the safety regulations and make a fun, quick car.

Mazda has gone great lengths to keep MX-5’s footprint close to the original and the scale tipping to the minimal. And unsurprisingly, the MX-5 has gained universal praise.

There are bigger cars out there that move quicker than the MX-5 in a straight line, but they also have hundreds more kilowatts to move the extra metal.

The extra heft just ruins performance in turns, destroys tyres faster and necessitates burning more fuel. Colin Chapman knew it, Mazda knows it, you should know it: size matters.