It’s the end of the line in New Zealand for the mid-sized Citroen C5 range – and with it goes one of the motoring world’s best innovations, the hydro-pneumatic suspension system.

The slow-selling C5 and Peugeot 508 sedan and wagon have been discontinued and will be replaced next year by altogether new models. “We’ve run out of C5 – same with 508,” said Peugeot-Citroen NZ divisional manager Simon Rose.

“We took the view that the sedan segment was declining, that (Peugeot-Citroen) SUVs were coming, so we said let’s get out (of sedans).

“We are in year of rationalisation for both brands. We are simplifying the business – we can’t have too many models. Same with Australia – they’re doing the same thing.”

It’s likely that the C5 will be the last mid-size passenger car carrying the Citroen badge. A replacement would likely come under the DS label, Citroen’s new premium brand.

Indeed, Citroen CEO Linda Jackson has said there was a “question mark” over the future of C5 outside of the Chinese market, where mid-size and large sedans sell well. (Jackson has been named by the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders as the “most influential British woman in the car industry.”)

The seven-year-old C5 is the last car to use the in-house hydro-pneumatic suspension, first seen in 1954 on the rear axle of the Traction Avant but on all four corners of the famous DS 19 model in 1955. It replaced traditional leaf springs and shock absorbers.

Variations of the system have since been used in flagship Citroen models. The C5’s is called Hydractive III. Peugeot Citroen CEO Carlos Tavares scrapped it last year as part of cost-cutting measures, and Jackson herself said it was “old technology.” She said future Citroens would provide comparably smooth rides by using new technology.

“Comfort suspension is 100 per cent part of our DNA,” she said. Newer technology such as computer-assisted semi-active systems have allowed carmakers to provide the advantages of hydro-pneumatic but at a lower cost.

Six decades ago the ground-breaking system was viewed as a mechanical marvel, wowing all with its adjustable ride height and self-levelling ride quality. It is simple in operation, based on the fact that a gas can be compressed but a fluid cannot. But nevertheless it earned a reputation for complexity.

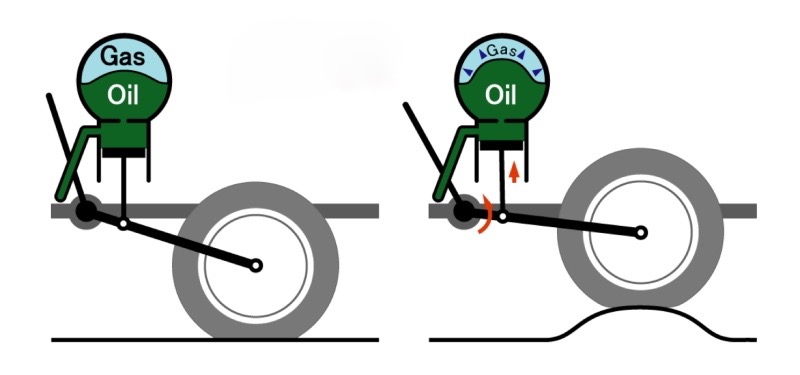

Citroen replaced leaf springs and shock absorbers – used by pretty much every carmaker back then – with pneumatic spheres at each wheel. One half of the sphere was filled with trapped nitrogen gas; the other with hydraulic fluid pressurised by an engine-driven pump.

The gas acts as the spring; the fluid as the shock absorber. The movement of other suspension components – control arms and swing arms – pushes the fluid around to compress gas in the spheres to smooth out bumps in the road and provide a pillowy ride.

A bonus was self-levelling suspension, so efficient that that the DS and subsequent models could be driven on three wheels without the ride height being affected.

The efficiency of self-levelling was aptly demonstrated by the BBC’s regular coverage of horse racing in Europe. For years its camera teams used Citroen Safaris to keep cameras on an even keel while filming the field from inside the rails.