Woulda, coulda, shoulda … the celebrated Holden nameplate might have survived if the carmaker’s board of directors in Australia had listened to its most senior engineer 23 years ago.

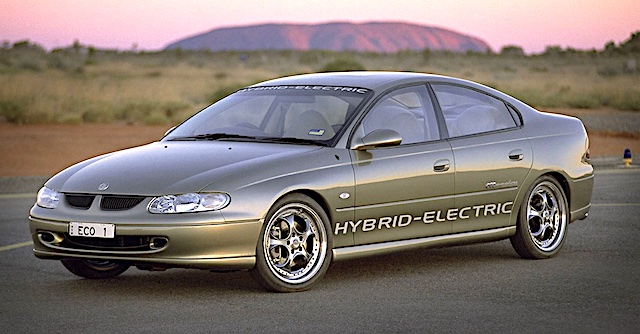

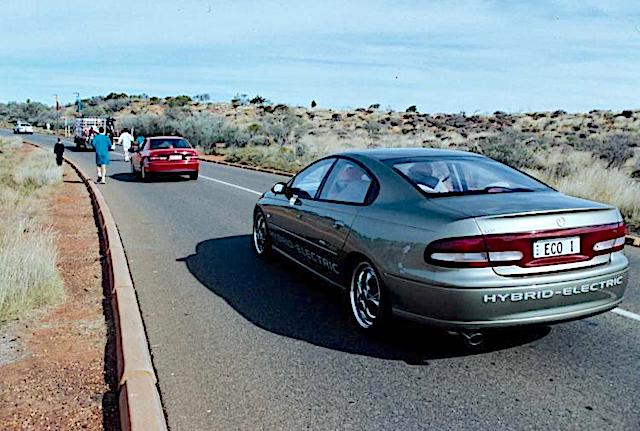

It was the year of the Sydney Olympic Games. Holden and the Australian Government’s CSIRO – Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation – had developed a hybrid ECOmmodore sedan, using components from 26 domestic suppliers. They began the project in 1998 and went public with it in June 2020 to showcase go-ahead Australian know-how to an Olympic audience.

The concept used a 2.0-litre, four-cylinder, petrol engine from the Holden Vectra. It developed 95kW and was mated to a 50kW electric motor charged by lead acid batteries backed up by super-capacitors. Drive went to the front wheels via a five-speed manual gearbox. The 45-litre fuel tank had a range of 800km, reckoned Holden.

The car was designed to show how fuel consumption could be almost halved and exhaust emissions cut by 10%-20% compared with the V6 Commodore, then the best-selling passenger car in Australia and New Zealand. The V6 produced 304Nm at 4000rpm. The hybrid made 290Nm at 4000rpm but had 100Nm on tap from rest, thanks to the electric motor.

The engine and motor worked either simultaneously or independently, depending on the driving conditions. The electric motor doubled as a generator when the conventional engine was driving the car, charging the battery and supercapacitor storage for later use.

However, the car was powered by electricity alone most of the time, only relying on the conventional engine when the energy supply needed topping up. The car also used regenerative braking.

The ECOmmodore shell had been redesigned to save weight and cut aerodynamic drag. Back then a VT Series II Commodore had a coefficient of drag of about 0.32; the ECOmmodore had a drag rating of 0.28. The hybrid weighed around 1700kg, slightly more than the standard Commodore.

Dr Laurie Sparke, the then head of innovation for Holden and who led the carmaker’s two-year collaboration with the CSIRO, said he told the Holden board of directors that hybrid technology was vital for the company’s future success.

“Their response was: ‘our customers want V8s, they don’t want electric cars’,” Sparke told the Sydney Morning Herald in a story on how Australia can best benefit from the growth in EVs.

“It was clearly the way of the future – it was what we had to do,” he said. “Environmental issues were already of great concern – fuel economy, emissions, global warming – even at that stage.” The world’s first production hybrid, the Toyota Prius, was still more than a year away from going on sale in Australia and New Zealand.

Holden and the CSRIO agreed at the time that public acceptance of a hybrid Commodore was still some years away and, anyway, building such a car for sale would take about eight years. The hybrid project was mothballed.

Now, six years after Holden, Ford, and Toyota closed their last Australasian assembly plants, EV advocates predict enormous opportunities for mineral-rich Australia.

It has some of the world’s biggest known reserves of metals that go into EVs and the batteries that power them. It is already the world’s top producer of lithium, and among the biggest producers of nickel, cobalt, manganese ore and rare earths.

The International Energy Agency estimates demand for EV batteries will grow more than tenfold this decade, stretching production capacity and supply of the materials that go into them.

World EV sales are quickly becoming an important economic driver for Australia. Exports of the minerals they use like copper, nickel and lithium were worth $NZ24 billion last year and forecast by its government agencies to hit $NZ36 billion this year.

Robyn Denholm, the Australian-born chair of Elon Musk’s Tesla, the world’s biggest EV maker, says the company is on track to spend more than $NZ1 billion a year on lithium, nickel and other metals mined in Australia.

Rather than just digging up minerals and watching others get rich with them, she says Australia should drive the dawn of a new industry further up the value chain. China dominates the EV battery value chain. It’s where 97 per cent of Australia’s lithium is processed and it makes three-quarters of the world’s battery cells.

Lessening the reliance on China is a major concern for Western governments. European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said last year that rare earths would soon be more important than oil and gas and that the bloc “must avoid becoming dependent again, as we did with oil and gas”.

The Australian government last year opened consultations on the country’s first electric vehicle strategy, aimed at developing policies to encourage “manufacturing of EVs, chargers and components”.

Sparke – who at times appeared in New Zealand for Holden product launches – finished his 43-year career at Holden in 2007 and set up his own EV start-up, EDay Life, which folded 10 years later after it was unable to attract enough investor support.

He told the Sydney Morning Herald he hopes Australia will finally grasp that EVs are a chance to restore some of the high-skilled jobs and advanced manufacturing know-how that was lost when the domestic auto industry shut down.

“I think it’s essential for Australia and the welfare of the community to get this growing,” he says. “Australia was able to be at the leading edge of a lot of stuff, and it all got blown away.”