• NZ Autocar magazine pays tribute to Chris Amon in its next edition, due August 25. This story will be part of the special feature.

Chris Amon laughed at the yarn about Carroll Shelby, the larger-than-life American motorsport legend, who helped Amon and fellow Kiwi Bruce McLaren win the 1966 Le Mans 24-hour race.

Shelby was from Texas. He told Texas-big stories and handed out Texas-big insults. Things like: “That idiot couldn’t pour water out of a boot if the instructions were written on the heel.” One of his stories was about his early days in the 1950s, on shabby racetracks in America’s South.

“These tracks weren’t fancy,” said Shelby, “so everybody worked on their cars in the shade. This one track had a peach orchard next to it. This guy was working real hard on his supercharger, the kind that stuck up through the hood.

“So when he left, I just packed that air scoop with peaches. Handfuls of ’em. When he came back and fired it up, you never heard such cussin’. Oh, he was mad. It smelled just like peach cobbler.”

Amon recalled it after Shelby died in 2012. “That was just like Carroll,” Amon said. “He was special – very important to me. He made things happen. He became a lifelong friend. His Cobra and Mustangs weren’t everyone’s cup of tea but they remain iconic. I hope he’s remembered up there with the likes of Enzo Ferrari and Henry Ford.”

Shelby was 89 when he died. The heart transplant he received in 1990 had done its dash. Same with the kidney transplant. Shelby had more non-stock parts than a Shelby Mustang, they said.

Amon died last week in Rotorua hospital. Cancer it was. He was 73. His death meant he didn’t get to keep a date in California with the car in which he and McLaren won with at Le Mans – the Ford GT40, chassis number P/1046.

That very car will be the star attraction at the Pebble Beach Concours d’Elegance next weekend. It’s an annual extravaganza near Monterey, and Amon was holding out for it. “It’s going to depend entirely on my health,” he told me weeks ago.

“I’m certainly going to have a go at getting there, but I’m going to have to improve quite a bit. It’s not the flight, that’s probably the easiest part of it. It’s coping with the schedule when I get there.”

Ford wanted Amon in Monterey. They wanted him at Le Mans in June for the 50th anniversary celebrations, but he wasn’t well enough to travel. They would have wanted Shelby, too – he was team manager back in ’66, when his Shelby-American Ford GT40s finished one-two. Another American team finished third. Shelby’s team won again in ’67.

Shelby also won Le Mans as a driver, sharing an Aston Martin in 1959 with Englishman Roy Salvadori and popping nitroglycerine pills under his tongue to help his ailing heart. The win in France came six months after he’d finished fourth in a Maserati 250F in the New Zealand GP at Ardmore.

Shelby stopped racing in 1960. “Doctor told me I was gonna die if I didn’t,” he said. “Gave me five years at most. I said I didn’t mind dying in a race. Then he asked who else dies when my car crashes.”

Amon drove for Shelby on and off between 1963-66. “He ran a really good operation, not always in easy times, either,” said Amon. “In his own way he was another Enzo Ferrari, although he didn’t have the diversity of Ferrari.

“A lasting impression of Carroll as a team leader was his wonderful calmness. In the last few hours at Le Mans in 1966 he was under severe pressure from Ford to make all sorts of decisions. Henry Ford was there – but Carroll remained unflappable.

“He assembled the best people around him,” said Amon. “He had a knack for it. Carroll once said, ‘You better learn to work with people because they’re the only thing you have to make anything work.’”

Orchestrating the first win for Ford at Le Mans was one of Shelby’s proudest moments. But Amon’s most vivid recollection of the annual endurance race came a year later. He’d signed for Ferrari late in ’66 and was driving one of three 330 P3/P4 models in 1967.

He’d already won at Daytona and Monza and Ferrari were confident about Le Mans. It was late at night. The story perhaps serves best to sum up the frustrations he would endure with broken Ferraris over the next two years. (In 1968 alone, he started on the front row in eight of 11 GPs, but something always gave out).

“I got a puncture in the right-rear tyre and the suspension upright was scraping on the track,” Amon said of the ’67 Le Mans. “There were sparks everywhere. I had about seven miles [11.2km] or so to go before I could pit and change tyres.

“Back then there was a toolbox in the cars, so I decided to stop and change the tyre myself. We carried a smaller get-home tyre for emergencies.

“I got the torch out of the toolbox to see what I was doing in the dark, but the torch wouldn’t work. So I took the hammer I needed to loosen the wheel hub and waited for the headlights of the other cars to give me some light.

“It was on the Mulsanne Straight. You have to remember that the cars were doing around 190-200mph [307-325km/h] going past me, so I didn’t have much time to see what I was doing.

“I took a swing at the wheel hub as a car flashed past but the head of the hammer flew off into the dark. I got back in the P4 and drove off. It caught fire from the sparks soon after and I jumped out and watched it eventually drift off the track and into a ditch.

“Gendarmes ran to it and flew into a panic because they couldn’t see the driver. They nearly died when I walked up and tapped one of them on the shoulder.”

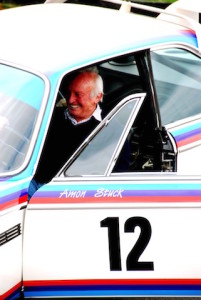

Amon took another drive down memory lane a few years ago when BMW wheeled out the car nicknamed the “Batmobile”. It was on the driveway of his farm near Taupo.

He had not seen the BMW 3.0CSL for 38 years, since he and German driver Hans-Joachim Stuck won the German six-hour at the Nurburgring, the fourth round of the 1973 European Touring Car Championship.

BMW had brought it from its motorsport museum in Munich, specifically for the New Zealand Festival of Motor Racing, at Hampton Downs that year. The 3.0CSL was valued at $1.5 million. It was specially built in 1972 for the championship, with a five-speed gearbox and 3.3- and 3.5-litre straight-six engines, good for about 275km/h.

Amon walked around it, smiled at its four wide, slick tyres and the “Amon Stuck” pairing on the door. He ran a hand over the bodywork and massive rear wing, opened the driver’s door and settled down behind the wheel.

“I don’t remember if this is the actual driver’s seat from 1973, but it feels good,” he said.

Amon’s career from the early 1960s through to 1973 had been pretty much confined to F1 and low-slung sports racers like the Ford GT40, Ferrari 330 P3/P4, and McLaren Can-Am cars, among others.

“I found the CSL touring car quite a handful after Formula One,” he said. “There is more roll, more vertical movement. You are sitting a lot higher, not that that makes a lot of difference.

“But it took me a while to adapt to the car. You don’t have the same degree of surplus of power in a touring car as you have in Formula One. You tend to overdrive them at first, and you end up going slower.”

Amon’s first drive in the CSL was at practice in Austria for the four-hour Salzburg race, the second event on the 1973 calendar after Monza. “Then it snowed so they cancelled the race. I can’t remember doing a lot of testing after that.”

Amon and Stuck missed the next race at Sweden’s Mantorp Park but lined up for the fourth event and a win in the German six-hour at the Nurburgring. CSLs finished one, two and three. Niki Lauda grabbed pole, set the fastest lap, and came in third. Dutchman Toine Hezemans, Austrian Dieter Quester, and German Harald Menzel took second place, eight seconds behind Amon and Stuck.

“I was still getting used to the car,” said Amon. “Stuck was very good and the worst thing is to be slower than your teammate. The next [24-hour] race at Spa gave me the chance to have two- and three-hours stints at the wheel. Then I was sort of on the pace.”

But back to Amon’s mate Shelby and another story. Shelby was taking a US motoring writer in a souped-up car around the Chrysler proving ground. The track had a steep hill for brake testing, with a hidden left turn at the bottom. Shelby showed the writer how to get some air under the tyres before coming down right to left to point in at the turn.

“Now I’ll show you the fast way,” Shelby told his passenger. He roared up the hill at the same angle but much faster. Just as the writer braced to go airborne, Shelby tapped the brakes. The front wheels never left the ground and Shelby kept the throttle floored all the way down the hill.

“You can’t accelerate while you’re in the air,” Shelby chuckled. Amon grinned, too. “Yep, that was Carroll,” he said. “He was a helluva good guy.” Shelby once said the same about Amon.