Chris Amon has a date in California in August that he would dearly love to keep.

It’s a one-on-one with the restored Ford GT40 MkII (above) in which he and fellow Kiwi Bruce McLaren won the Le Mans 24-hour race in 1966.

Chassis P/1046 will be the star attraction this year at the Pebble Beach Concourse d’Elegance, an annual extravaganza near Monterey.

The racer is on display at Le Mans this weekend, a historic showpiece supporting Ford’s modern-day return to the French circuit 50 years after the GT40s’ famous 1-2-3 finish.

Amon, 72, was invited to Le Mans as Ford’s guest of honour, but health issues after major surgery forced him to cancel. His London-based son Alex is representing him.

“I tried to go but I had to flag it about a month ago,” Amon said on the eve of this weekend’s classic.

“Ford want me to go to Monterey, but it’s going to depend entirely on my health. I’m certainly going to have a go at getting there but I’m going to have to improve quite a bit.

“It’s not the flight, that’s probably the easiest part of it. It’s coping with the schedule when I get there.”

Amon, 72, is the last survivor of the six men who piloted the Mark II GT40s and their 7.0-litre V8 engines to the first three places in 1966. McLaren and Amon won in car No.2; fellow Kiwi Denny Hulme and US-based Englishman Ken Miles were second in car No.1; and Americans Ron Bucknum and Dick Hutcherson third in car No.5.

Miles died weeks after the race, crashing in California while testing a planned successor to the GT40 MkII; McLaren died in a test crash in 1970; Hulme from a heart attack during the 1992 Mt Panorama race; Bucknum from diabetes complications in 1992; Hutcherson from a heart attack in 2005.

The 1996 result ended Ferrari’s domination of the French classic and entered in US Ford teams, the first two cars flying the Shelby-American banner and managed by US motorsport legend Carroll Shelby, and the third car by Holman and Moody, Ford’s longtime racing contractor.

Shelby died in 2012, aged 89. The heart transplant he’d received in 1990 had done its dash. Same with the kidney transplant. Shelby had more stock parts than a Shelby Mustang, they said.

Amon drove for Shelby on and off for three years in the 1960s. “He was a helluva good guy, very important to me,” said Amon.

“Carroll ran a really good operation, not always in easy times either. In his own way he was another (Enzo) Ferrari, although he didn’t have the diversity of Ferrari.

“A lasting impression of Carroll as team leader was his wonderful calmness. In the last few hours at Le Mans in 1966 he was under severe pressure from Ford to make all sort of decisions. Henry Ford was there – but Carroll remained unflappable.”

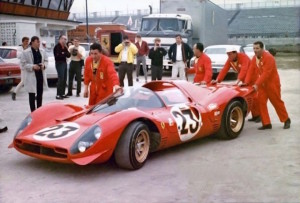

Amon moved to Ferrari in 1967, partnering Italian Lorenzo Bandini in Formula One and sports racers. Ferrari had been embarrassed by the Ford 1-2-3 clean sweep the year before and wanted payback.

It had prepared four 330 P4 cars and their 4.2-litre V12 engines for Le Mans that year – three dedicated P4s and an earlier P3 model, updated to P4 specifications and called the P3/4.

Amon first drove the P4 in the United States early in ‘67, when he and Bandini won the Daytona 24-hour race. They won again soon after in Italy, in the Monza 1000.

“It was funny in ’67,” said Amon. “We’d won at Daytona and Monza and Ferrari were all gung-ho and saying we’re going to go to Le Mans and win.

“I told the Ferrari guys, ‘Hang on a second, this is going to be a hard ask.’ That’s exactly how it turned out. Ford had run the MkIV on a test day at Le Mans in ’66 and I knew the potential it had.”

The Ferrari P4s finished second and third behind the Shelby-American team’s Ford GT40 MkIV. The third P4 retired on lap 296. Amon’s P3/4 died on lap 105. The car was on fire in a ditch.

Shelby and his all-American team won again in 1968 with a GT40, for an historic personal three-peat. Another GT40 won in ’69.

By all accounts Shelby – a maverick Texan who told Texas-big stories – often chuckled at the way his mate Amon’s race ended in 1967.

Amon tells the story: “I got a puncture in the right-rear tyre of the P4 and the suspension upright was scraping on the track.

“There were sparks everywhere. I had about seven miles [11.2km] or so to go before I could pit and change tyres.

“Back then there was a toolbox and a small jack in the cars, so I decided to stop and change the tyre myself. We carried a smaller get-home tyre for emergencies.

“I got the torch out of the toolbox to see what I was doing in the dark, but the torch wouldn’t work.

“So I took the hammer I needed to loosen the wheel hub and waited for the headlights of the other cars to give me some light.

“It was on the Mulsanne Straight. The cars were doing around 190mph [307km/h] going past me, so I didn’t have much time to see what I was doing.

“I took a swing at the wheel as a car flashed past but the head of the hammer flew off. I got back in the P4 and drove off.

“It caught fire from the sparks soon after and I jumped out and watched it eventually drift off the track and into a ditch.

“Gendarmes ran to it and flew into a panic because they couldn’t see the driver. They nearly died when I walked up and tapped one of them on the shoulder.”