Between 8am and 9am on a cold Thursday morning in Norway last February, five million Norwegians used as much electricity as 10 million residents of neighbouring Sweden.

The reason, reported news agency Bloomberg, was not just because of the large number of electric cars (BEVs) being charged in Norway, but also the prevalence of electric heating in the country. Electricity is used to warm around 85% of all indoor spaces in Norway.

Those factors have contributed to Norway having the second-highest electricity consumption per capita in the world, surpassed only by Iceland, which gets 73% of its electricity from hydro power – from the flow of water – and 27% from geothermal.

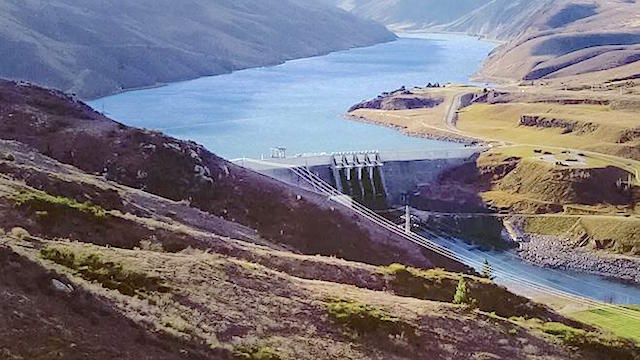

Norway gets around 98% of its electricity from hydro power. The remaining 2% comes from gas plants and wind farms. New Zealand gets around 80% of electricity from renewables – hydro, geothermal, wind – and 20% from fossil fuels – coal, oil, gas – some of which are imported.

Norway has around 1200 (twelve hundred) hydro power plants of varying generating capacity. Three are near the city of Bergen, the wettest area in Western Europe. New Zealand has around 100 hydro and geothermal plants (one hundred), again of varying capacity.

Norway expects its domestic electricity consumption to grow 30% by 2040. Studies show peak demand for electricity in New Zealand could grow by 40% by 2040.

So what’s going to generate the extra electricity needed to power all the light BEVs the recent Climate Change Commission (CCC) report recommends New Zealanders need to be driving after 2035, the year it proposes a ban on petrol and diesel imports in the drive to cut greenhouse gas emissions by 2050?

Will it be increased renewable hydro production, via a strengthening of the grid, like hydro leader Norway is doing? Or a fallback on non-renewable coal, oil and gas, the fossil fuels the CCC wants phased out?

A case in point: Electricity from coal increased 43% in New Zealand 2019, when domestic demand for electricity increased but water levels in hydro lakes fell and natural gas was in short supply. Coal imports that year rose by 90%.

It’s clear the CCC report borrowed from the script global BEV leader Norway uses. Transport Minister Michael Wood borrowed from it too. He said a discount – from July 1 – on low-emission vehicles funded somewhat by a fee on higher emitting vehicles was “common policy overseas.”

Christina Bu is secretary-general of the Norwegian Electric Vehicle Association (NEVA). She was an exchange student in New Zealand in the late 1990s, and in her professional role has been back a few times to talk to government, energy companies, automotive distributors, and BEV groups about how transport in Norway is going all-electric.

“What I found interesting from the discussions was that New Zealand says it can increase its electricity energy production a lot,” she said from Oslo. “The problem is, unlike Norway, it cannot export it.”

Norway shares its borders with countries wanting to buy its surplus electricity. New Zealand shares its borders with lots of salt water. Since 2016, Norway has exported upwards of 10% of annual domestic electricity production.

“Norway is sort of a big battery,” said Bu. “We can sell the hydro energy to Europe for high prices and import it back when prices are low.”

The country is seeking to become the first nation to end the sale of petrol and diesel cars by 2025. It currently exempts all BEVs from the taxes imposed on internal combustion engines.

As a result, 54% of all new cars sold in Norway last year were powered by batteries only – a global record – up from 42% in 2019 and a mere 1% a decade ago.

The policy comes at a substantial cost, estimated by Norway’s ruling centre-right coalition at US$2.32 billion in lost state revenue last year, or some US$29,000 on average for each new electric car sold.

But while Norway might have dropped a couple of billion dollars on BEVs in 2020, its Government Pension Fund Global, which indirectly helps to prop up BEV policy, earned 53 times that in the same year – US$125 billion.

The state fund, also known as the oil fund (pub talk is the pension pot), was set up in the 1990s to invest government revenues from Norway’s enormous fossil fuel reserves into sectors deemed more sustainable.

“Oil companies are actually subsidised by the state fund to find oil, but of course they pay way more back to the government in taxes,” said Bu. “They are heavily taxed. That’s why Norway is a wealthy country.”

The state fund has grown into one of the biggest single stores of wealth in the world, and the largest sovereign wealth fund controlled by a country on behalf of its citizens. It was last month sitting on around US$1.3 trillion in assets.

It holds stakes in more than 9000 companies worldwide, owning 1.5 per cent of all listed stocks. Then there are bonds and real estate, including some of the best commercial and residential addresses.

The fund invests only abroad so that Norway’s economy does not overheat. The government borrows from the oil fund to plug budget deficits every year.

Meanwhile, Norway is betting on hydrogen and offshore wind for its energy transition but will continue to extract oil and gas until 2050 and beyond, its government said this month.

It wants to strengthen the national power grid in order to make better use of its hydro-electric energy supply, which faces future high demand. Why strengthen the existing grid? “It currently takes too long to plan and approve new grid installations,” said Minister of Petroleum and Energy Tina Bru.

Norway plans to use hydro-electric power to cut emissions from its offshore network of oil and gas platforms. It expects oil and gas extraction will naturally decline by 65% by 2050.

Norway’s vow to keep producing oil comes as energy firms come under growing investor pressure to shift away from fossil fuels. It also runs counter to an appeal from the world’s top energy body, the International Energy Agency (IEA), to stop investing in new oil and gas projects by next year.

Few governments worldwide, say international analysts, are likely to follow as closely as necessary the script laid out by the IEA to eliminate greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 or risk devastating climatic consequences.

The IEA report argues that such a transition is possible – it would just be hellishly hard. Cutting the environmental impact while advancing living standards worldwide would require “a singular, unwavering focus from all governments, working together with one another, and with businesses, investors and citizens,” it says.

The CCC report says New Zealand has a “harder job” ahead if it’s to meet its 2050 obligations as a signatory to the Paris climate agreement. This country’s C02 emissions – from transport, industry, farming, and so on – continue to rise. Transport alone accounts for 20% of total greenhouse emissions.

Politicians were warned last century that the country’s car fleet was getting dirtier. In 1999, 56 per cent of used imports from Japan and elsewhere were eight years old or more, up from 44 per cent in 1998.

Analysis back then by the National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA) found that the average eight-year-old car produced two-and-a-half times as much hydrocarbon and over five times as much nitrogen oxides as the average new car.

A government report in 2002 said transport was responsible for 44% of New Zealand’s carbon dioxide emissions and around 16% of total greenhouse gas emissions.

What’s needed, said observers at the time, was a C02 emissions test as part of the Warrant of Fitness inspection. But nothing was done. Why? Because used imports and old New Zealand-new cars comprised the bulk of the country’s car fleet, and even the most rudimentary WoF emissions test going into the 21st century would likely have ruled many of them off the road.

In 2006, the then coalition government’s Climate Change Minister David Parker (the current Attorney General) told the NZ Herald that further action was needed to meet climate change objectives.

“The energy outlook to 2030 shows that if we do not change our policy settings, transport greenhouse gas emissions will increase by 45 per cent over the next 25 years. We cannot, and will not, let that happen,” he said.

Now, after many more years of emissions inertia from Labour- and National-led coalitions, New Zealand is to get something like a smelly exhaust test. It’s called the Clean Car Standard and comes into place in 2023.

Look for a hike in the price of new and imported used cars that don’t meet the C02 requirements. It’s likely, say two car industry managing directors, to range between $2000 and $15,000.