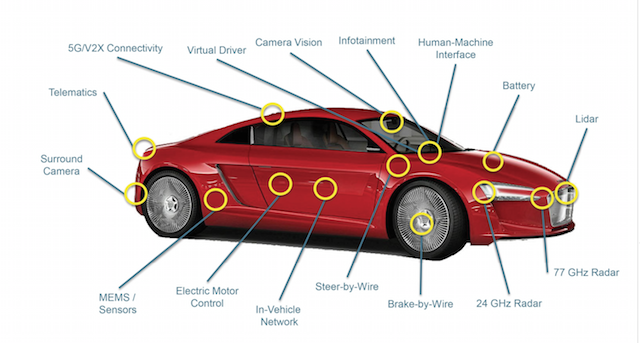

The car, over the next 10 years or so, will become a consumer electronics product full of micro-processors. “It will have 80 to 100 software controllers – in the end it will work like a smartphone,” Volkswagen Group CEO Herbert Diess has said.

But the switch to battery-electric propulsion from the internal combustion engine will not be as great a change in terms of production as some think, he said. “Yes, the drivetrain is changing but the car remains a car. There’ll be seats and screens, an interior, rims and wheels … 70 per cent of the car will remain the same. But the car itself will be more sophisticated.”

Diess said that while Elon Musk and Tesla largely paved the way, electrification would have happened anyway, “because people are realising that we need to drive down C02 emissions and the only way to achieve this is with EVs.”

Volkswagen lays claim to the auto industry’s biggest push into electric cars with a five-year investment plan worth more than NZ$50 billion. Diess, a key driver of VW’s electric-car initiatives, and Musk have exchanged compliments in the past. The former BMW executive has repeatedly hailed Tesla’s technological achievements, while Musk has said the VW chief is doing more than any other major carmaker to go electric.

More than 12 countries have set a date for phasing out fossil-fueled light vehicles. Norway, where around 55 per cent of new car sales in 2020 were electric vehicles, wants done with them by 2025. The New Zealand Government is eyeing 2032. Carmakers themselves have pledged to go all-EV. Rival nameplates are working together to meet self-imposed EV deadlines.

But what about battery development for EVs? Where is that going? Batteries in 2032 model year cars will be more energy dense for greater range than the lithium-ion examples in today’s EVs. They almost certainly won’t be as volatile, say physicists.

In a lithium-ion battery, charged lithium particles travel through a barrier in the electrolyte from the anode (the negative end) to the cathode (the positive end), where they undergo a chemical reaction that produces energy.

Most lithium-ion electrolytes are a mix of flammable lithium salts and toxic liquids. If the permeable barrier that separates the cathode from the anode crumbles, it creates a short circuit—and a fire risk.

Aqueous batteries avoid all these problems, with electrolytes that are water-based and therefore both nonflammable and nontoxic. They’ve been around for 25 years but have been too weak to be useful.

For the past few years a team of US researchers led by physicists at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory have been developing a lithium-ion aqueous battery that’s seemingly immune to failure. It can be cut, shot, bent, and soaked without an interruption in power.

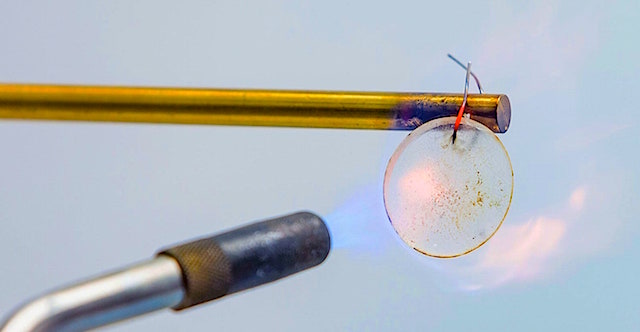

Late last year, the team pushed it further, making it fireproof and boosting its voltages to levels comparable with a commercial product. By increasing the concentration of lithium salts and mixing the electrolyte with a polymer—a material resembling a soft plastic—the team found they could bump the electric potential from around 1.2 volts to 4 volts, which is comparable with commercial lithium-ion batteries.

When they attached a commercially available anode and cathode to this plasticky electrolyte, they ended up with a lithium-ion battery unlike anything ever seen. It’s clear and flexible like a contact lens, nontoxic and nonflammable, and can be manufactured and operated in the open air without a case. On top of that, it can withstand pretty much any kind of abuse.

During tests, the team submerged the device in salt water, cut it with scissors, used an air cannon to simulate a ballistic impact, and lit it on fire. Through each test, the battery kept pumping out electricity. After one trial by fire, the charred portion was cut off and it continued to operate normally for 100 hours.

The new water-based battery isn’t just a laboratory curiosity, says the team. It is already in talks with undisclosed manufacturers who they say could integrate the new chemistry and form factor into existing lithium-ion production facilities without much difficulty.

Because it is flexible, it could be incorporated into wearable electronics, even eventually integrated directly into clothing fiber. Its ruggedness also suggests new uses in a host of military and scientific applications, such as autonomous underwater vehicles, drones, and satellites.

There are still a few technical hurdles to overcome, such as increasing the number of charging cycles an aqueous battery can handle. A typical smartphone battery can be recharged well over 1000 times, but this battery begins to lose efficiency after just 100 cycles. Fine-tuning the electrolyte chemistry should provide a fix, say the researchers.