Electric vehicles (EVs) are doomed as a long-term transport solution because charging times for batteries will never fall to practical levels, says a senior Lexus executive.

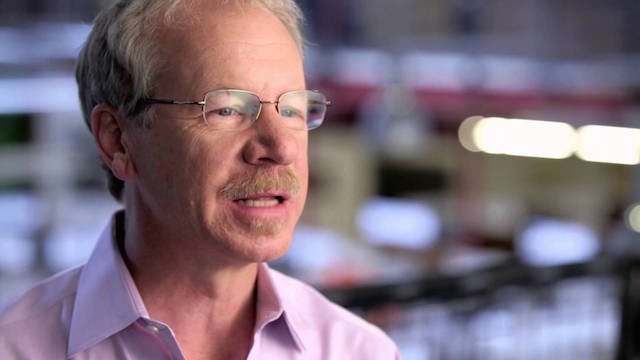

It’s “a simple matter of chemistry,” said American Paul Williamsen, the luxury carmaker’s global communications manager. “We won’t be able to get charging times down.”

Williamsen said he had worked with batteries long enough to know that fast-charging a battery was about the second-worst thing that could be done to it. He targeted EV carmaker Tesla and its Superchargers.

“There are two ways to abuse a battery: overheat it, or fast charge it,” he said. “With the Tesla Superchargers, they don’t publicise it, but if you ‘supercharge’ a Tesla, one supercharge takes 20 charge cycles off the end of that battery’s life. Two supercharges takes 40 charges.

“That’s simple chemistry. You can’t force the ions through the battery that fast without causing damage.”

He said the reason Lexus and its parent company Toyota had largely stuck with internal-combustion engines and hybrids was because a “smart company” like Toyota wouldn’t bother investing too much money in a form of propulsion that would soon be redundant.

“It’s not that we’re not working on EVs at all, and I think there is a place for them, just in cities, for some small, luxury vehicles for commuting,” said Williamsen.

His comments come four years after Tesla CEO Elon Musk labelled fuel cell vehicles “bullshit” and hydrogen gas “dangerous.” Musk was unveiling a Tesla service centre in Germany at the time and said hydrogen was a “dangerous kind of gas, suitable for the upper stages of rockets, but not for cars.”

He criticised the safety and practicality of hydrogen as an alternative energy source. “The reality is that if you take the best case for a fuel cell vehicle in terms of the mass and volume required to go a particular range, as well as the cost of the fuel cell system, it doesn’t even equal the current state-of-the-art lithium-ion batteries, so there is no way for it to be a workable technology,” Musk said.

But Williamsen said the only energy source that made long-term sense was hydrogen. “You can make a motor vehicle that uses hydrogen as an energy source in three completely unrelated ways,” he said.

“The only one that makes sense is a hydrogen/EV hybrid. That’s what we’re doing, and we’re using our experience in hybrid to do that.

“If you don’t make your hydrogen car a hybrid, you’re giving up all the efficiency advantages of regeneration. So you’re being wasteful.

“Our approach is to have the best and most efficient way of using hydrogen, which has to be a hybrid. Not every automaker thinks that way.

“They can have a zero-emission vehicle by having a hydrogen fuel cell that directly drives the car, or a hydrogen powered ICE (internal combustion engine), but they’re using twice as much hydrogen as we are.

“We believe a hydrogen fuel-cell EV hybrid is the only way to go, so that’s all we build.”

Toyota has a fuel-cell car on sale in Japan and America. It’s the Mirai (it means ‘future’ in Japanese), a front-drive sedan (pictured at top) 4.9m long, 1.82m wide. It has a fairly typical suspension system – MacPherson struts at the front and double wishbones at the rear.

Two large air intakes on each side of the Mirai’s grille pull in hydrogen and oxygen from the air to feed the fuel-cell stack. The chemical reaction creates electricity to drive the vehicle.

The Mirai has two hydrogen fuel tanks, one under the front seats and the other behind the rear seats. The stack itself is 50 per cent lighter than a prvious design and delivers 114kW of power and 330Nm of torque to the wheels via a six-speed gearbox.