It’s being called the world’s first commercially available energy system that uses new or existing rooftop solar panels to create and store hydrogen power in a battery about the size of a large refrigerator.

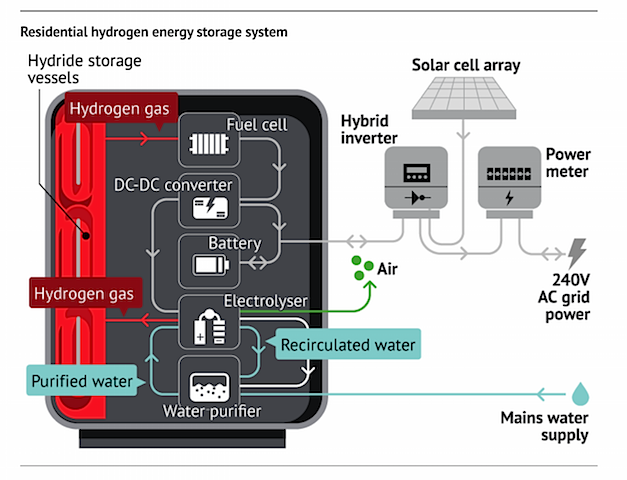

Weighing 324kg, it sits outside the house or business and connects to a solar inverter and the mains water through a purification unit. Inside it, electrolysers use the solar power to convert water into hydrogen and oxygen.

The oxygen is vented and the hydrogen stored at 30bar, or 435psi, in a patented hydride ‘sponge’ in removable canisters inside the unit. The hydride is a fibrous metal alloy not dissimilar to iron-filings in appearance.

It stores some 40 kilowatt-hours worth of energy, three times as much as Tesla’s current Powerwall 2. It uses a fuel cell to deliver energy into the home, adding a small 5-kWh lithium buffer battery for instantaneous response.

Businesses with higher power needs can run several in parallel to form an “intelligent virtual power plant.” There’s Wi-Fi connectivity, and a phone app for monitoring and control.

It was developed by Australian company LAVO, working with the University of NSW in Sydney. LAVO’s chief executive, Alan Yu (pictured at top and bottom centre above with colleagues), told media that the unit can store enough power on a single charge to run the average household for two to three days.

Unlike other commercially available lithium batteries, it can also constantly recharge itself rather than waiting until it has been fully discharged.

Yu said the system, which costs around A$34,000, should last users around 30 years, roughly three times longer than other lithium-ion batteries.

Yu said the system, which costs around A$34,000, should last users around 30 years, roughly three times longer than other lithium-ion batteries.

When the hydride is degraded it can be melted down and reused, giving the system significant environmental advantages over its competitors.

The hydrogen is stored in a solid state inside the hydride, thus avoiding the risks of fire associated with hydrogen stored under pressure or in liquid form.

The battery would not only supply power, but users would be able to remove the canisters of charged hydride from their own units to power household items such as the barbecue and bicycle.

LAVO hopes that even people who have not bought the battery system might be able to use its hydrogen canisters on a ‘swap’ basis, like a Sodastream tank.

One Australian eco-lodge is already a customer. Gowings Bros, the investment company that evolved from the famous men’s clothing business, has agreed to buy 200 of the power units for its properties around Australia.

Professor Kondo-Francois Aguey-Zinsou (above), who leads the Hydrogen Energy Research Centre at the University of NSW, and has worked on the system with LAVO, said the hydride had the potential for much broader applications, including as a possible means of exporting hydrogen.

He said transporting hydrogen in LAVO cylinders would be safer and easier than shipping bulk hydrogen stored under pressure or converted into ammonia and reconverted back into hydrogen at point of use.

- The LAVO company is named after Antoine Lavoisier, the 18th century French chemist who is said to have given oxygen and hydrogen its names. He was executed by guillotine in 1794 – during the French Revolution – for adding water to tobacco, an experiment whipped up into a crime by a jealous rival, Jean-Paul Marat.