Let’s take a couple of upcoming electric vans to New Zealand as an example, the Ford Transit and LDV’s eDeliver 3, if only because they are square shaped with lots of sheet metal and serve a visual purpose.

One day, the battery pack that sits under the floor of each van won’t be there. The battery will be the van itself – chassis, bodyshell, floor, doors, mudguards, tailgate … This is the future world of ‘structural’ battery power, where composite materials that make up the vehicle’s frame store the energy needed to make it go.

Picture the Transit (at top) and eDeliver 3 (dismantled and complete below) with every exterior panel made of thin layers of composite material, say carbon-fibre. The carbon-fibre is infused with lithium-ions, part of the electrical storage chain.

Just recently, Tesla said it would soon have a car where the battery pack would be integrated into the chassis, a design that would reduce the car’s weight by 10 per cent and improve its range. Its CEO Elon Musk hailed the process as “revolutionary.”

But structural batteries were developed first by the US military about 10 years ago, using carbon-fibre as the cell’s electrodes. The material is malleable and could be applied to form, for instance, an airplane wing or a mudguard.

Since then, experts like Emile Greenhalgh, a materials scientist at Imperial College London and the engineering chair in emerging technologies at the Royal Academy, have erased the boundary between the battery and the object it powers.

“What we’re doing is going beyond what Elon Musk has been talking about,” Greenhalgh told US researchers. “There are no embedded batteries. The material itself is the energy storage device.”

Unlike a conventional battery pack, structural batteries are invisible. The electrical storage happens in the thin layers of composite materials that make up the car’s frame. In a sense, they’re weightless because the car is the battery.

“It’s making the material do two things simultaneously,” said Greenhalgh. The use of such technology, say researchers, can provide huge performance gains and improve safety because there won’t be thousands of energy-dense, flammable cells packed into the car.

In 2013, Volvo teamed with the Chalmers University of Technology in Sweden to integrate structural batteries into a prototype S80 sedan, a project funded by the European Union. At first scientists integrated lithium-ion batteries into a plenum cover that regulated air intake into the engine.

It wasn’t the car’s main battery, but a secondary pack that supplied electricity to the air-conditioning, stereo, and lights when the engine temporarily turned off at a stop light. Its strength permitted the integration of a strut brace, and its energy capacity allowed for the removal of the dedicated stop/start battery, saving 50 per cent in weight compared to the standard items.

Then the scientists developed a structural supercapacitor that was used as the boot lid. It consisted of two layers of carbon fiber infused with iron oxide and magnesium oxide, separated by an insulating layer and moulded into the shape of the boot. They also developed a spare wheel well from the same material.

Supercapacitors don’t hold nearly as much energy as a battery, but they’re great at rapidly delivering small amounts of electric charge. Greenhalgh said that they’re also easier to work with and were a necessary stepping stone toward accomplishing the same thing with a battery.

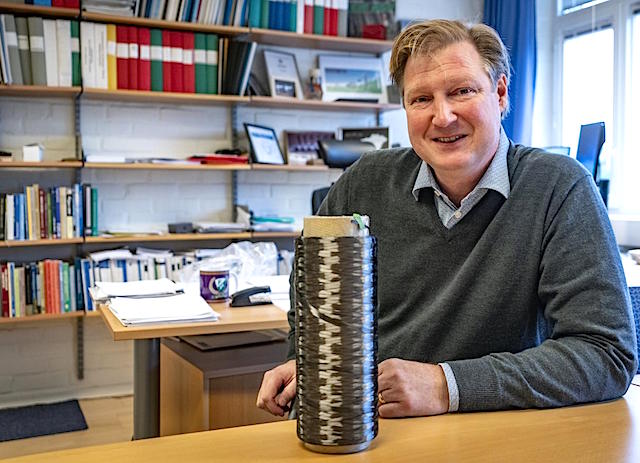

Greenhalgh’s main colleague on the project, Swedish scientist Leif Asp, said the main benefit of structural batteries is that they reduce the amount of energy an EV needs to drive the same distance, in effect increasing its range.

“We need to focus on energy efficiency,” says Asp. “In a world where most electricity is still produced with fossil fuels, every electron counts in the fight against climate change.”

In the US, University of Michigan chemical engineer Nicholas Kotov has built small robots that mimic animals. They include robotic scorpions and spiders that skitter around the floor, each powered by a structural battery integrated with their moving parts.

Unlike the carbon-fiber and lithium-ion sheets being developed by Asp and Greenhalgh, Kotov and his students created a zinc-air structural battery for their automatons.

This cell chemistry is able to store much more energy than conventional Lithium-ion cells. It consists of a zinc anode, a carbon cloth cathode, and a semi-rigid electrolyte made from polymer-based nanofibers that is nano-engineered to mimic cartilage.

The energy carriers in this type of battery are hydroxide ions that are produced when oxygen from the air interacts with the zinc. While structural batteries for vehicles are highly rigid, the cell developed by Kotov’s team is meant to be pliable to cope with the movements of the robots.

They’re also incredibly energy-dense. As Kotov and his team published earlier this year, their structural batteries have 72 times the energy capacity of a conventional lithium-ion cell of the same volume.